Mission statement

INTRODUCTION

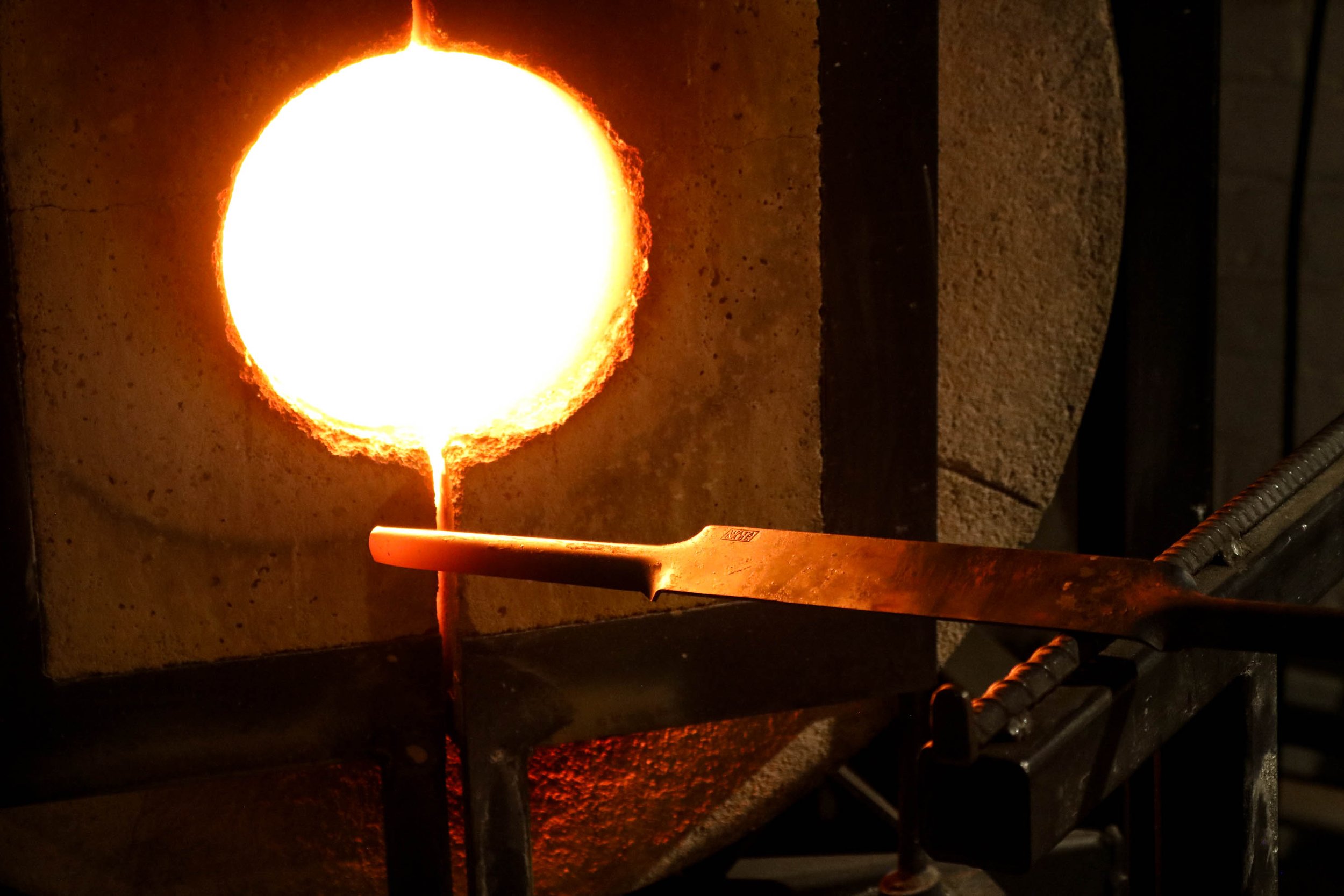

When reflecting on the importance of toolmaking to the glass industry, we can recall the cliché that we can never manipulate hot glass with our bare hands and we never have. Since the first experimental scooping of hot vitreous sand off the walls of the first pit fire ceramic furnaces 40,000 years ago until this very moment, we’ve always had a tool between us and the glass, whether it’s a rock, a bronze shaft, a fruitwood paddle, or a pair of Dinos. Tools are the liaison between us and the material.

And of course, to do what we need them to do, tools need to feel right and look right, perform right, simply be right. Tools possess a certain undefinable consciousness through which you can sense when they’re sharp or well balanced or if the material they’re cutting is in the right shape to be cut. Musicians talk about this with regard to their instruments - the violin needs to be in agreement with the bow and the bower. The instrument consciousness of guitars and horns needs to be felt to access their true tone.

I feel like jacks sort of sing like flutes when you’re behaving well and the material is behaving well and the stars are just right. But it’s not just spiritual magic - it’s metallurgical magic as well. It’s geometry and balance and weight and density and silicon and carbon and manganese content, as well as a smith’s attention to detail and compulsive (pathological) commitment to “more perfect.” To being in conversation with glassblowers outside the forge.

Tools can’t just be built for the blacksmith’s reflection in the polish, either, but for the glassblower’s layer of soot and wax that covers it up. Built to blend in with the tarnish of the bench and be tossed about by a craftsperson who is not focused on what the tool is, but on what it does. When tools are built right, they agree to disappear, and they do so in a seemingly conscious coordination with their bench-fellow.

This is what I’m after in my toolmaking practice: to make tools that speak to you but don’t shout (or squeak).

The second project I’m pursuing in this website is an archive dedicated to the craft of hand-forged glassblowing tools. I aim to assemble a more vivid historical account, consolidating information to consider why certain design decisions were made and when they were made. This will help us understand where not only the tools come from and why, but also how glass-making itself was affected by the innovation of new tool designs along the way. This also is a story of the way information traveled around the world through history, how tool makers in Paris and Lisbon and Prague and Markakesh and Cairo and Jerusalem and Barcelona may have all had an influence on those in Venice and vice versa.

I also wish to document the craftspeople who dedicated their lives to the forgotten art of hand-forged glassblowing tools - one that directly shaped the aesthetic of glass made through the ages. The maestros of the forge have had no audience and have left a poor paper trail. I want to dig up these stories and give them their due. I also want to create an audience for their legacy.

When I hear stories like that Lino put all these tools in his suitcase and brought them to Seattle in 1980 because the Americans were using grill tongs and butter knives, etc. I feel these stories matter. They’re a key part of the history of glassblowing.

HISTORY

The history of glassblowing tools has long been a passion project for me. I’ve begun to piece together certain narratives based on oral accounts, historical context, attention to the design evolution of glass, and a healthy dose of logical inference. I would love to secure funding to further my research and to turn this into a legitimate research project — for example by working with institutions like Venini, Salviati, Barovier, Seguso, Roberto Dona, Archangeli, and others to locate records that could shed light on some of this lost history.

But in the meantime, let me share some of the stories I’ve begun to tease out.

Jack, Ivan, Jeff and Jim

A while back in 2020, somebody sent me a photograph of a pair of Jack Rann shears. They had a marking that was incomplete, and it just looked like it said “KRANN” OR “J. RANN”, and he wanted to get some information on the tools. So I did some detective work and called around to see what I could come up with. I started in the UK, thinking that they looked English. I immediately came across a pair that had the beginning of that stamp which said “JACK RA”, and it was very easy to see that these two halves made a whole which spelled clearly “J. RANN” or in some cases “JACK RANN”. Because of the frequency of incomplete stamps, a lot of both the US and the UK folks I talked to thought his name was “Kran” or “Rand.” Once I had the information I needed, I was able to look around and find more shears made by Jack Rann - and designs of tools that varied from straight trim to custom crescent diamonds etc. All of these were very beautiful tools that were hand forged the old way: the handles have forge welded rings and serpentine stems, sometimes the handles have what we call “SOOS” handles like Jim Moore has paid beautiful tribute to with his absolutely classic Diamond shears. As soon as you start picking around for Jack Rann, you quickly discover fellow British blacksmith Ivan H. Smith (good name for a smith) examples in the mix and vice versa. Jack and Ivan were not making tools at the same time — Ivan was working in the final third of the twentieth century, and Rann, probably in the first third, if not earlier — but it’s clear that Ivan had Jack’s shears in hand when he designed his own. The two makers are often mistaken for each other, but once you know what to look for, it’s easy to pick Ivan Smith out of the pile. I should note here that Jack Rann was part of a wider scope of English tool-makers that worked in a tradition that goes back hundreds of years and more. So just because a tool may look old and clearly isn’t Ivan’s work, it does not mean that it must be Rann. There are many others who made work in this style; it’s just convenient that Rann, also a more contemporary smith, signed his work.

Between these two periods of hand-craftsmanship, just up the hill in Sweden up until the 1980s, smith Nathaniel Adolfsson was fast at work carving his own path in steel. Adolfsson was a traditional craftsman who expanded upon the Swedish glassblowing tool tradition to create intricate yet brutally simplistic works of art for the glass factory floor. Borrowing from the rich history of Lindstrom & Co., a Swedish tradition since 1856, as well as the newly formed Essemce AB (1947), Adolfsson utilized techniques like hard facing to fortify the cutting edges, and multiple alloy usage to diversify the metallurgy in his tools - for very specific purposes. His tools share a similar silhouette with Lindstrom and can often be confused if not for the bold logo Lindstrom uses (see Diamond Shears Fig. 9).

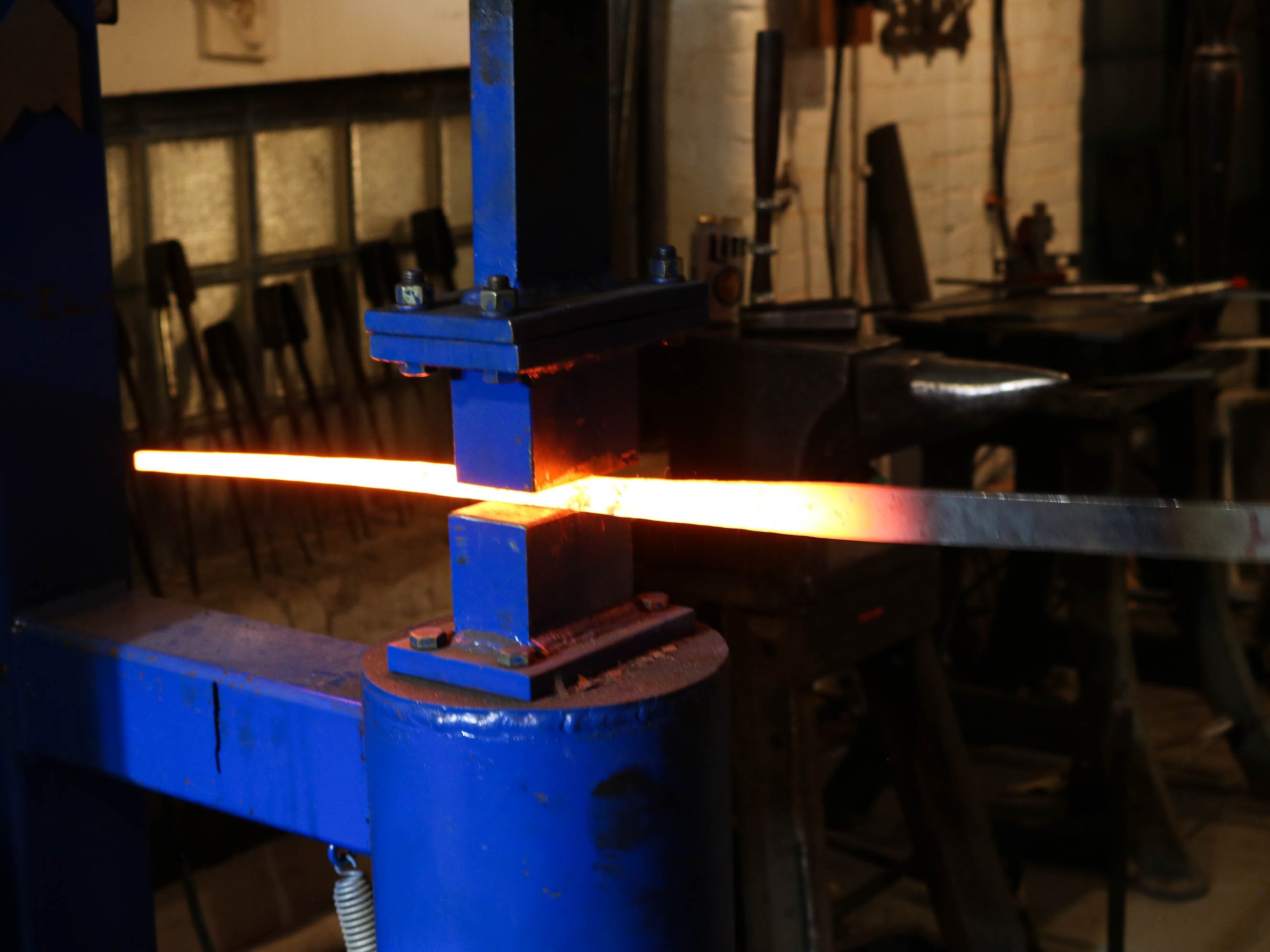

Ivan Smith, being an Englishman of a certain age, probably had access to tools made by Nathaniel Adolfsson as well as Linstrom & CO. Ivan was probably aware of Nathaniel Adolfsson and his work. They did share quite a bit in common: the two were glass-curious blacksmiths who made exquisite handcrafted tools for the glass industry in ‘the old way’. One key feature of Ivan’s tools that stands apart from other English tools like those made by Jack Rann is the hard facing of the blade’s cutting edge. I really do think that this very distinctly Swedish technique was something that Ivan was inspired by and that he decided to use in his process. Hard facing is the brazing of a very hard material like Stellite, or other nickel or chromium alloys into a groove carved at the cutting edge of a shear blade; it’s then ground flat and given an edge - which it keeps. The process allows you to use a “tougher” (forgiving) steel with less “hardness” (brittle) for the shear blade body, to absorb impact, while the cutting edge is made out of a super hard and sharp-staying material that would otherwise shatter upon impact. This is an exhaustive process for production and has been replaced by using tougher steels. Jim Moore used to hard face his shears back in the ‘80’s and they were awesome but I understand why he switched to just using a good tool steel - they last long enough for most purposes and are much faster to make without the hard facing.

What replaced the hard facing process - and improved upon the use of softer steels - was the use of D-2 tool steel that blends toughness and hardness in the right way. This was an innovation made by Jeff Lindsay in the early days of Cutting Edge glass tools. He took the famous Frankenstein shears of Dante Marioni and redesigned them for the modern age. Dante’s Gaios were so banged up and welded together multiple times. Instead of trying to revive them yet again, Jeff designed a new medium-format shear to be waterjet cut in D-2 which, once hardened, takes a not-very-sharp-edge and holds it forever…this is what we want. It was this lineage of Putsch to Gaio to Cutting Edge that really sent me down this rabbit hole.

(Left to right) Putsch medium diamond shears, Gaio Arturo medium diamond shears, Cutting Edge Dante shears

Jack Rann shears with partial stamp

Jack Rann shears with partial stamp

Arturo and Dona

Gaio Arturo was an incredible craftsman and innovator in the history of master glass tool design. He grew up in Maniago, a region of Italy known for knives, shears and tool making in general. After the war, Gaio came to Venice with a bike outfitted with a sharpening stone hooked up to the wheel. Upon seeing glassblowing shears, mostly Putsch, Fennek and some French stuff that had been circulating around the island for centuries, Gaio realized something had to be done about the poor geometry endemic in the glassblowing shear family. Gaio took Putsch and Putsch-Meniconi cutting tools and traced them. He changed certain features including the pipe grabbers and made more slender curvatures. He adjusted the handle geometry for smaller hands and adjusted the fulcrum placement for better action. He also hollow ground all of his shears and supplied a loose fitting bolt, so they would cut and handle like the fabric shears he was so used to sharpening and tuning. Looseness of fulcrum and hollow grinding allows glass chips and dust to not be trapped between the blades. Gaio made the shears lighter and swifter to wield. He made the tools in part at the Carlo Donà workshop, as he was a friend of the family. In fact, Donà didn’t start making shears until after Gaio’s retirement in ‘98. At the end of his life, Gaio left his equipment with the Donà’s to carry on the work. Roberto Donà invented a new line of cutting tools, making a unique line of shears that lead in the industry and have exquisite utility. I feel like even though shears were never a Muranese thing, Roby has made a line of cutting tools that feel like legacy objects that have always belonged in Murano.

Medieval Developments

The longer history of the glassblowing tools is largely undocumented, though it runs parallel with the history of the glass itself. In 1291, through government decree, the ruling Doge of Venice, Pietro Gradanigo exiled the glassworks from Venice and forced them to set up shop on the island of Murano. The official narrative being that of fire prevention and architectural preservation, yet other goals were clearly in focus.

Up until that time, since the seventh century, according to archaeological findings on the Island of Torcello, and as early as the fifth century according to the documented resettlement of glassmakers from abroad, many of the workshops were based on the island of Venice. Many of these workshops had their own wood and metal shops that employed in-house tools, molds, equipment, and maintenance. Many workshops also shared common toolmakers and handymen. This ecosystem was dramatically affected by the downsizing that needed to take place in order to reestablish business and rebuild furnaces and production systems on the island of Murano.

The reason for the move to Murano was documented as to prevent the loss of historic art, architecture and infrastructure due to the frequency of fires and to prevent further damage to the growing city. It is widely understood that the real reason for the move was to isolate the glassmakers on an island north of Venice so that their secrets would be better protected from a bustling international city of commerce and trade. Following a law passed in 1295, glassmakers were prevented from leaving the island without a permit. This, however, did come with a caveat that the glassmakers attained an elevated class of nobility for their service.

This move coincided with the official end of the Crusades, when the loss of the cities Tyre and Acre to the Mamluks in 1291 ended the open trade relationship with Venice. Up until that point, the trade network between Venice and Tyre provided the Venetian glass industry with, among other commodities, silica, alum, manganese oxide, salt, lead, tin, copper, sulfur, and soda ash. Tyre was likely shipping raw components directly to Venice until this period. This would have been a point at which glass houses needed to radically adjust chemistries and formulas to accommodate new raw material sourcing. This period of experimentation, innovation and consolidation birthed an explosive new era in glass making out of necessity.

During this consolidation and restructuring, tool making, pipe making, mold making, equipment design and furnace building all required a jumpstart. New facilities had to be established so the new factories could be built and stocked with equipment. It is possible that this faction of the industry was government funded in order to lubricate the process.

We figure that this is when tool houses similar to the contemporary Archangeli Murano, Carlo Dona, and Dino Tedeschi began to serve the greater glassblowing community in favor of the old way in which each individual glass house took care of its own. I believe it was a similar system that the glassmakers fell into, where the tool families had their particular ways of doing things and that they passed their legacy and techniques down from generation to generation. This type of middle-age and Renaissance era tool-house-family lineage is one of the sweet spots of tool innovation that I want to investigate.

Onwards

In more recent memory, the 20th century was booming on the Island of Murano. After much of the nineteenth century in which the glass makers were largely inactive, the establishment of glasshouses like Barovier & Toso, Salviati & C, Cappellin & Venini, and Artisti Barovier, there was suddenly a renewed demand for tools. I am interested in finding the names of these tool makers and examples of work they accomplished. There is clearly a much more recent lineage to document and one that has had lasting implications on the way we interact with glass to this day and beyond.